Picture this. It’s an average summer morning, except it looks a little cloudy outside. You decide to shut off the AC, open a few windows and get the fans going before you head out. On your way home from work it starts to pour. Heavily. You think….I knew it might rain, I should’ve closed the windows! Truthfully, at the time you never really knew it was going to rain, did you? Not to mention, neither did the weatherman.

This is what we call hindsight bias. We believe after a specific event occurred that we had enough knowledge to predict the event.

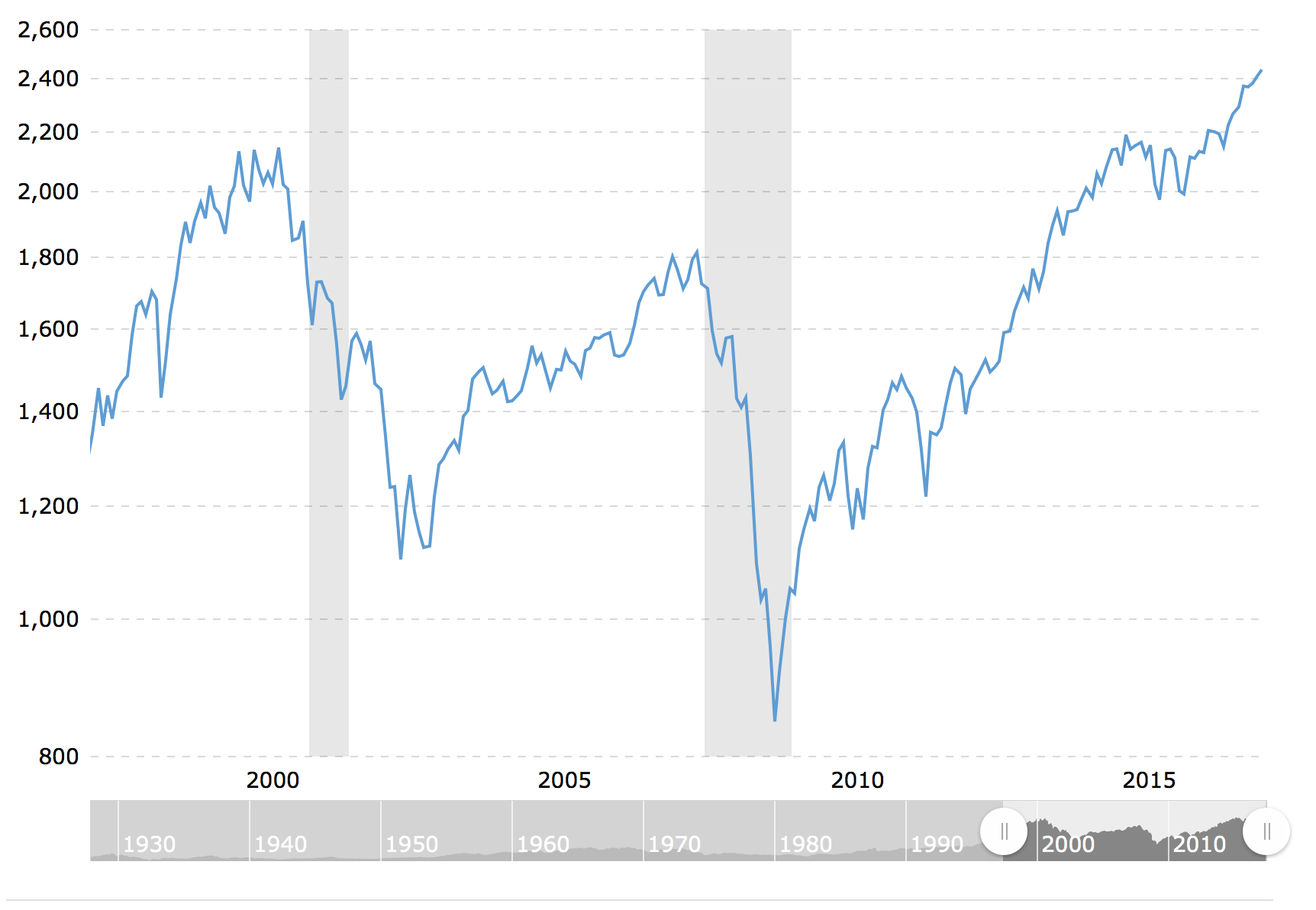

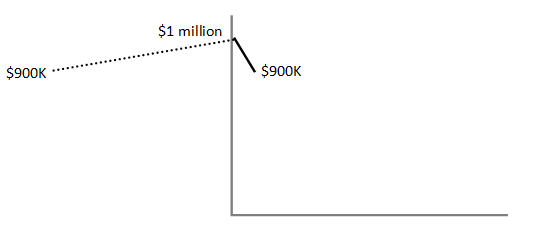

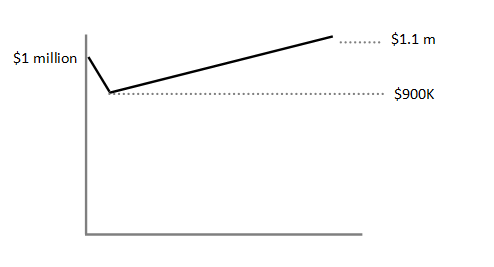

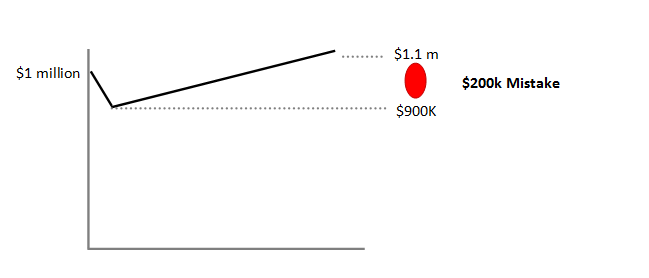

Investors develop hindsight bias by becoming reactive to any new information they receive. There is a famous story of Sir Isaac Newton who was a victim of hindsight bias. He sold out of an investment thinking he got out at the top. While all of his friends stayed invested, he watched as they double and tripled their original investment. All the while, he was kicking himself for selling out early (Hindsight bias at work). And then he famously bought back into this investment at the very top. It quickly plummeted and left him almost broke. But he didn’t learn his lesson. He went on to make a number of other poor investment decisions that left him penniless.

Why are we so susceptible to hindsight bias? Psychology tells us that humans have a need to create order. So in a way we are attempting to learn from our mistakes by oversimplifying the causes of a certain outcome. In the real world, there are too many variables to account for. Usually, we pretend like we had the knowledge to make the correct decision at the time when we really did not. This type of bias makes it difficult to learn from our past mistakes, we don’t stop and review what really occurred and why. By believing one’s ability to predict future events, an investor can develop ‘overconfidence’ while attempting to predict future events in the market. Consequences can arise when investors attempt to make informed decisions with an unrealistic view of risk leading to mediocre returns, or worse, losses.

It is important for investors to recognize this bias so they can prevent it from spoiling their judgments while making important investment decisions.

This post was written by our intern, Dan Varghese.