February’s issue of the Journal of Financial Planning included a flowchart I developed a few months ago to help guide clients through the rules around taking distributions from 529 Plans. Here is a link to the flowchart if you have questions about how 529 plans work.

What Drives the Cost of College

With all of our clients who have children, planning for college expenses is the one of the biggest concerns that keeps them up at night. Retirement planning may be a bigger issue in the long term, but the children will be going to college a lot sooner than their parents will retire.

As I work on putting together plans for clients to balance their own retirement and send their kids to a good college, I find myself stepping back wondering how college became so expensive. Since the mid 1980s, the cost of college has increased 500%! And it continues to grow faster than inflation. Today’s students are graduating with a mountain of debt. In fact, there is now more student loan debt than credit card debt.

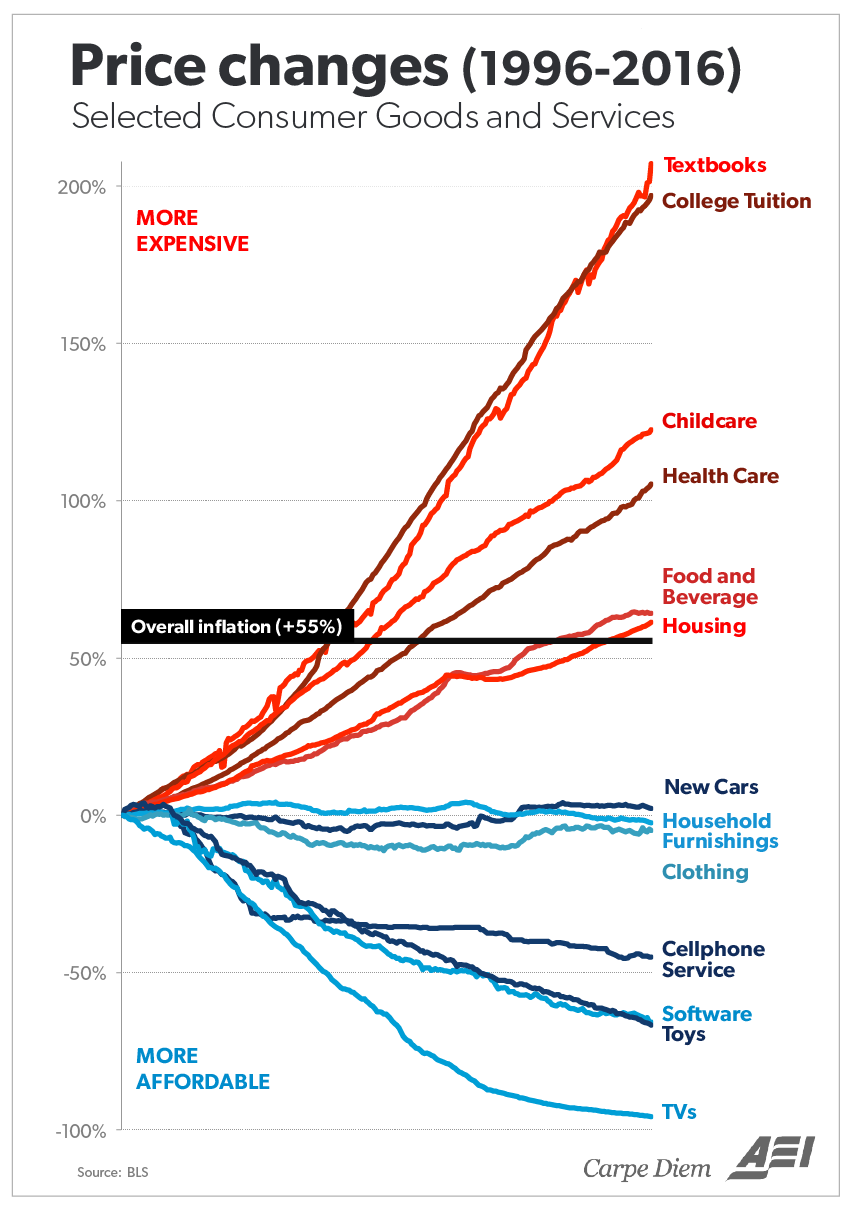

Just look at this chart to see how out of control college costs have gotten over the last twenty years:

What does this chart say? Over the last twenty years, items in blue have actually gotten cheaper. TV’s, software, toys, cars and clothing are all cheaper than they were twenty years ago. The items in red, such as housing, food, health care, childcare and COLLEGE have gotten more expensive over the years. As much as we complain about the escalating cost of healthcare, it’s not nearly as bad as college.

How did we arrive at this problem? A simple answer is that money is freely available for people to borrow to pay for college. The cost does not become a big driver in the decision making process when there are grants, scholarships, tax credits, and even loans involved that mitigate the financial bite. This results in universities having to offer more services, bigger buildings, better facilities, etc in an effort to attract students who are not as cost conscious as before.

With the government stepping in to provide assistance (loans and tax credits), they are actually contributing to the problem and making it worse. They are creating a gap between the perceived cost a student pays to go to college and the actual cost to attend.

This happened with real estate when the government wanted everyone to own their own home – loans and incentives fueled the market. The good intentions of the government backfired as people were given mortgages they couldn’t actually afford, which spurred housing prices to soar… for a while at least.

A similar problem exists in health insurance. The insured are insulated from the true cost of a service because the health insurance pays for most of the expenses incurred.

If you’re interested in reading more about this and seeing the kinds of solutions that might work, I found this article to be a fascinating read on the subject of college costs.

Five Creative Uses for a 529 Plan

What should you do if you have extra money in a 529 College Savings Plan? Perhaps it’s left over funds used to pay for a child’s education or perhaps the child has opted not to go to college.

The common options are to change the beneficiary (to a different child or relative). But that may not be practical. Below are a few interesting ideas I’ve stumbled across over the years:

Outward Bound (Website)– This outdoor educational institution teaches people of all ages about wilderness expeditions and training. Many of their courses accept payment from 529 plans. (Details)

Study Abroad – There are examples of some people taking an educational trip abroad through a university. If set up correctly, funds from 529 can be used. (Details)

The Culinary Institute of America (Website) – One of the most respected cooking institutes in the world allows most of their college course programs to be paid for using money from a 529 plan.

Pursue a hobby – An example in this article references an individual who started a small maple-syrup farm. He wanted to learn a lot more about the science behind what he was doing and ended up taking horticulture classes at his local community college. (Details)

Go to graduate school – Maybe the children are done with undergrad. In that case, maybe they will eventually go for a master’s degree. The 529 can be used for that too.

How To Save, When You Can’t Save Today

“ I want to save for retirement, but I can’t afford to do so right now.”

This is a common complaint we hear, especially with our younger clients. They are dealing with debts, saving for their children’s education, and even helping to take care of their aging parents. These younger clients want to save for retirement but just don’t know what to do.

So, what should they do?

Over the last few months I have written about this concept extensively:

Is a Creative Saving Strategy Right For Me?

The Most overlooked Saving Strategy: The Serial Payment

The Three Flaws With The Most Popular Saving Strategy

The strategy that I outline is to come up with a plan to consistently save more and more every year. Perhaps you save an extra 1% of your paycheck each year, or every year allocate a portion of your raise to retirement. This concept is also referred to as Saving For Tomorrow, Tomorrow and there is a great Ted Talk about it here.

If you’re on board with this concept, visit this New York Times calculator to see how this could work for you: One Percent More Calculator

Einstein is claimed to have said that “Compounding interest is the eighth wonder of the world”. And by combining the benefits of compounding interest and compounding savings into a retirement plan, it would make for a much, much more powerful strategy.

Is a Creative Saving Strategy Right for Me?

Someone can reach an ambitious financial goal (such as saving for college education) despite having limited cash flow available to fund the goal. The goal can be accomplished by using a creative saving strategy called a serial payment.

Many clients that I have worked with this year have expressed a strong desire to fund a majority of their children’s college education but currently have limited resources to commit to it today. Instead, they have promising careers in which they expect decent raises in the future or expect their spouse to re-enter the workforce once the children are in school. They have already tightened their belt and understand that a portion of future raises will be diverted to their future goals. This strategy gives them a roadmap for the future.

For more details, read these other posts to learn about the process.

The Most Overlooked Saving Strategy: The Serial Payment

In a recent post, I argued that there is a flaw in the most common approach saving for a big goal like college education.

I argue that in some cases, saving for a goal should be done the way you would if you were to begin training for a road race. If you begin to exercise today and have a goal of running in a marathon twelve months from now, you won’t just start running 26.2 miles per day. You’ll burn out or get injured.

Instead, you are more likely to come up with a plan where you gradually and systematically increase the difficulty of your exercise regimen over time. By gradually increasing the workout, you mentally condition yourself and can prepare for longer, harder, and more difficult exercise routines in preparation for the race.

While we mostly think about saving a set dollar amount per month, that may not be realistic or possible for many people who have limited cash flow. Saving for a goal could be done the same way by using a saving strategy referred to as the serial payment. Here is what makes this strategy different – the amount saved increases by a set percentage each and every year. For example someone who saves $150 a month for one year, would increase it by a set percentage (we’ll say 4%) each and every year. In year 2, they would be saving $156/mo ($150 * 1.04). In year 3, they would be saving $162 ($156 * 1.04).

Let’s compare these two strategies. Assume that John and Andrew each want to save $90,000 for college education in 18 years. They plan to save a portion of their paycheck and will invest it in the market where they are expecting an 8% rate of return. John plans to invest $2400 at the end of every year and will do so for 18 years. Andrew will fund $1,825 at the end of the year but will increase the amount by 4% per year thereafter.

The result: they both reach their goal of $90,000 by the end of the 18th year. Below is the breakdown of how much each of them has to save each year:

Andrew is able to begin saving a lot less early on but will have to make up for it from the 9th year and on. By then he will likely be in the peak earning years of his career and will have more cash available to fund the goal.

This strategy does have some drawbacks. Making less contributions in the early years reduces the effectiveness of compounding interest which means that Andrew would have to save an extra $3500 more than John over the 18 years. And that figure would be much larger if we adjusted for inflation.

If you are exploring ways to save for a goal, run the numbers assuming a flat/fixed amount first. Saving more earlier is almost always preferable thanks to compounding interest. But it may not be possible. If you can’t afford that, try using a serial payment strategy.